The Evolution of Egyptian Art

When you think of ancient Egyptian art, what most likely comes to mind is the Great Sphinx of Giza or the Pyramids and while Egyptian architecture and statues are certainly very impressive, they are only a small part of a very intricate yet specific artistic culture. The Egyptians loved to paint, to draw and to carve, using mineral pigments to create bright reds, golds, greens, blues and black. They were usually then coated with a varnish which has enabled many items to last remarkably well.

The style is very distinctive, generally based around pharaohs, sphinxes and the many Egyptian gods. Always intended to be functional rather than beautiful, artistic creations served as homes for spirits and gods; gifts to the afterlife; or to appease a pharaoh, and the theme of balance was prevalent throughout. The history of their art is almost as old as that of the Ancient Egyptian civilisation itself and changed very little over the 3000 years that the society reigned over the river Nile. Perhaps that is why it is very easy for even the untrained eye to notice a work of art from the time.

Identifying Egyptian Art

The earliest Egyptian art can be easily identified by the images of the people in their paintings. These depictions are sized depending on status, with gods and pharaohs being painted much larger than the average person, who in turn will be bigger than their slaves who were considered to be the lowest form of human life. Animals, trees and inanimate objects were also kept small and less significant.

Most striking, perhaps, is the ways these people are represented, with their bodies always facing the onlooker and their heads looking to the side. Men are shaded darker than women and when standing, the people always have their legs parted. There was no sense of perspective in any of their creations, so that everything seemed very two-dimensional.

Monuments

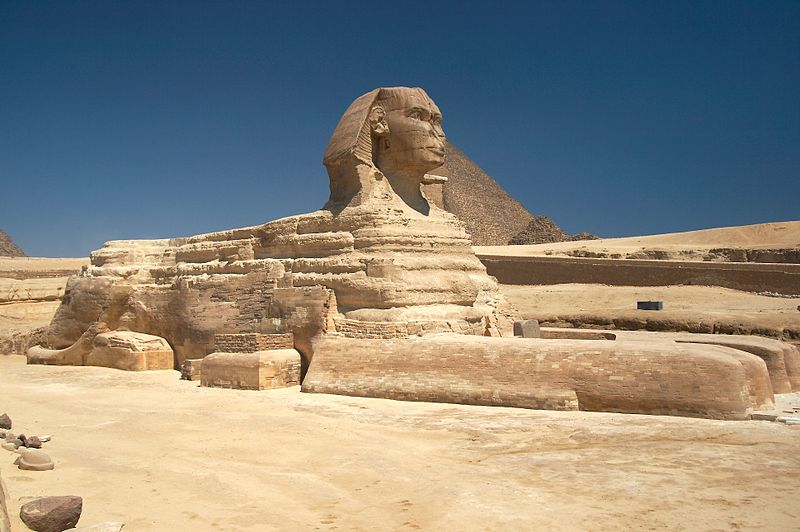

Pharaohs would often commission large statues that would require a large team of artists to work together to create. Perhaps the most famous example of this is the Great Sphinx of Giza, which would have taken around three years to complete. The sphinx is a mythical Egyptian creation that had the body of a lion and a human head. When depicted in art, these creatures would usually wear a headdress similar to those the pharaohs wore.

The giant statue was carved out of limestone and historians have dated it around 2500BC, although this has been highly contested by many and few agree on who built it and why. Although the statue today looks fairly monotone in colour, pigment residue suggests it would have been painted when it was built, making for a far more spectacular sight.

Sphinxes became more popular in Egyptian art during the reign of Thutmose. Legend has it that, as a young prince, Thutmose once fell asleep in the shadow of the Great Sphinx and had a dream. In it, the Sphinx spoke to him and told him to clear the sand around the base of the statue in order to become the next king. When he was finally crowned, he regularly commissioned works to include his favourite mythical creature. There is also a plaque in front of the Sphinx that tells this story.

Bas-Relief

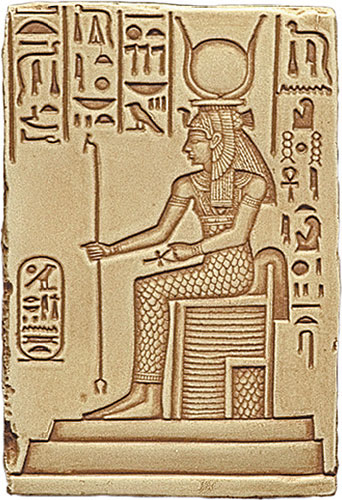

A very common feature in statues and carvings, bas-relief (pronounced bah ree-leef) is a term for when the carved figures are raised from their background. The Egyptians liked to add their bas-relief designs to the side of existing stone buildings, giving them a distinct and unique look.

While bas-relief can be created through simply carving away at a wall, the Egyptians were more dedicated to perfection. They would apply a thin layer of plaster to the side of a building and then polish it until perfectly smooth. One of the team of artists would then mark the plastered area with a red cross pattern which would make it easier to keep the correct proportion of the figures. They would have an image on a piece of papyrus that would have been drawn by the lead artist and this would be copied exactly onto the wall. The sculptor would then come along and carve the image using a wooden mallet and copper chisel. Paint was then used to further accentuate the creation.

Hieroglyphics

As much an artistic expression as a way of communicating, the word ‘hieroglyphics’ literally means ‘holy writings’ and were used as a way to help people remember the names of the various pharaohs. There was a symbolic alphabet of sorts, but since their language is so different to ours, it is very difficult to match the hieroglyphs to the English alphabet. Symbols would usually stand for certain sounds, but also, sometimes they were a representation of the figure or item.

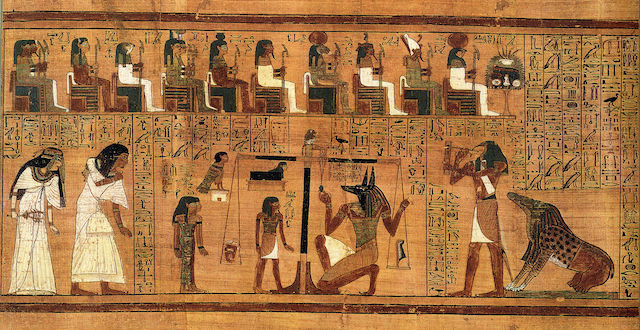

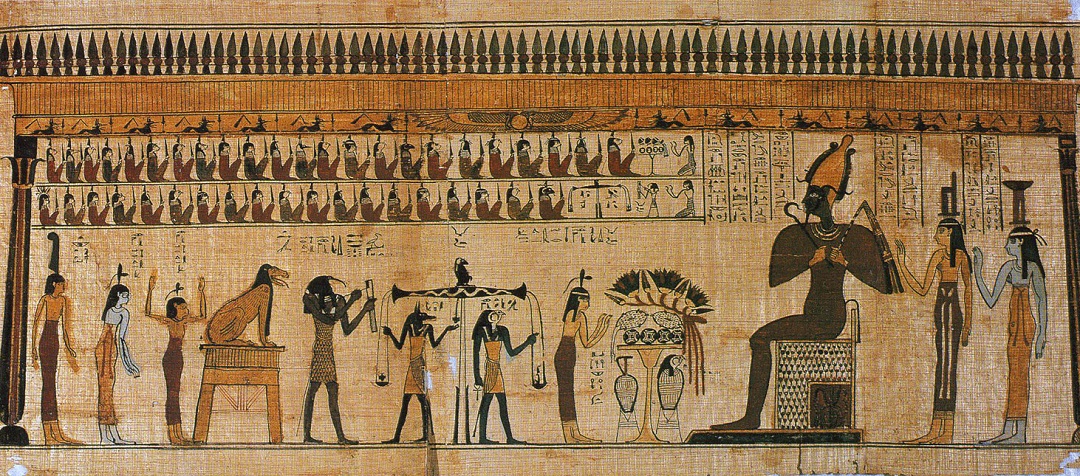

Hieroglyphs were not used for day-to-day communication but were instead considered to be a gift from the god, reserved for art works ordered by the pharaoh in order to carry some sort of magical power. One famous example of this is the Egyptian Book of the Dead, a scroll made to protect certain wealthy figures in the afterlife. There were a number of them made, many of which would unroll to around 17-feet long. They were painted with hieroglyphs to represent magic spells that were intended to protect them, as well as images from their home and people that they loved, in order to bring them comfort, and then buried with them when they died.

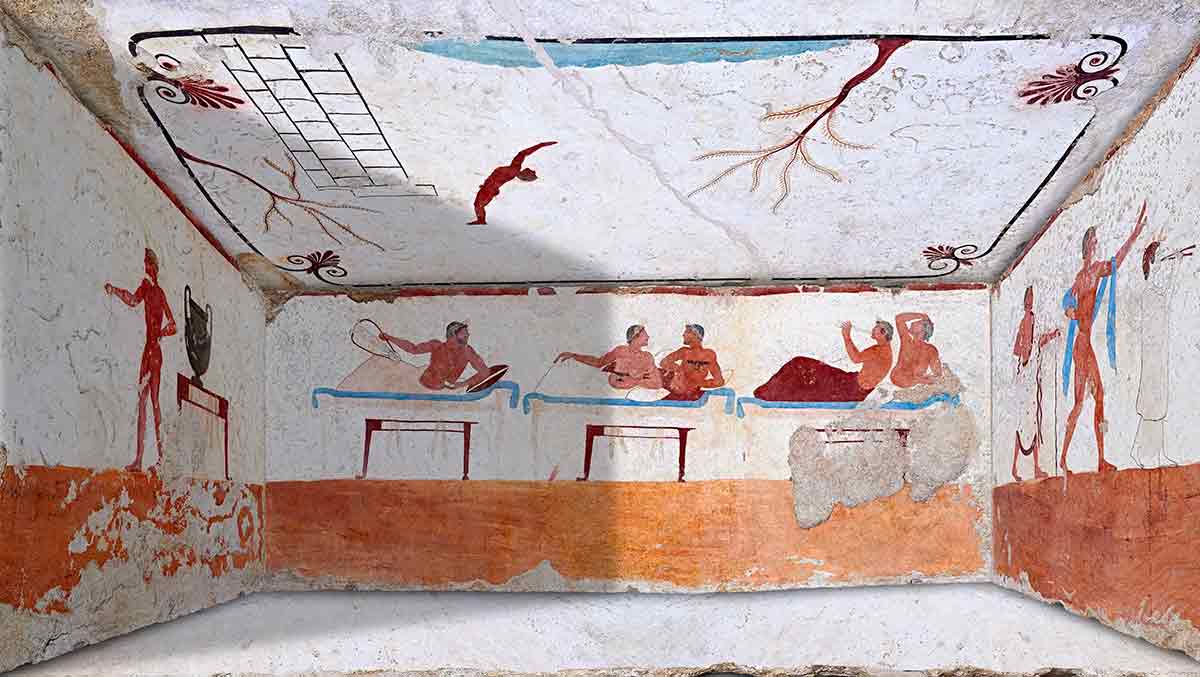

Those rich and powerful enough to have a tomb prepared for their body would also have had it decorated with hundreds of paintings. These were never intended to be seen by outsiders but were carved as a mark of respect for the dead body within. They would often represent the deceased passing into the next life, or the happy times they hoped they would have in their death, accompanied by beautiful hieroglyphic markings. They would also often leave small sculptures of ‘gifts’ they wanted their loved one to take with them into the afterlife.

Amarna Art

A unique form of art that became prominent in the eighteenth dynasty. Gone were the traditional chiselled bodies of previous paintings – instead men were depicted with more feminine features including large breasts and lips. These images had a more fluid sense of movement in them that went against the years of artistic structured convention.

This change came about with the reign of a new king – Akhenaten. A huge devotee to Aten, the God representing a sun disk, his new stylised form of art came as part of a new religious cult set up in order to honour this deity. Aten was different to other gods of the time in that it had no human form but it soon became the official state god. Even architecture of the time was different to buildings of the past, in that they had a more open style to them, in order to let the sun in.

During his reign, Akhenaten married Nefertiti and she features in many of the art pieces of the time. The Bust of Nefertiti is one of the most famous, painted with stucco materials. She is thought to have been an extremely beautiful woman, since statues and paintings at this time were created to be realistic rather than idealistic. In contrast, Akhenaten is usually shown as having overly large lips, a long chin and a large head. Another famous painting from the time is of two of their daughters, Neferneferuaten Tasherit and Neferneferure, both with a more fluid, less structured form.

After Akhenaten’s death, Egyptian art returned to its conservative, strict traditional style, with many works of art and architecture of this time being destroyed and the former king’s name stricken from official records.

Modern-Day Art

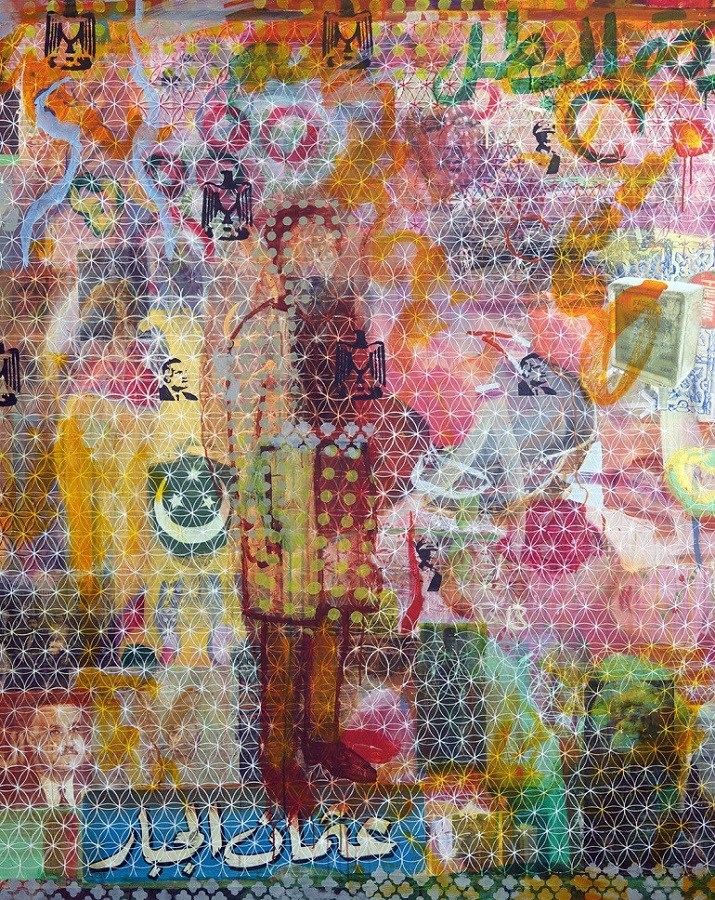

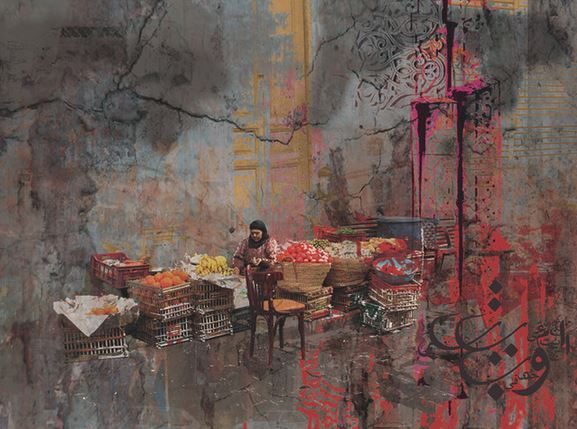

Egyptians have always expressed their artistic creativity through carvings and paintings on walls and the citizens today are no different. Modern art is a response to the toppling of the government in 2011, with graffiti-like images splashed across Cairo showing the feelings of the people. While most street art is quickly painted over, as if it never existed, there are a few artists who have made their name in this way. Names to look out for include Alaa Awad, Hazem Taha Hussein and Hossam Dirar.

Images are now freer with fewer restrictions, but in the case of Awad and Hussein, there is still an element of tradition running through their wall murals, with that familiar Egyptian pose and repetitive nature. The difference now, however, is that many artists have a political agenda attached to their work. It is no longer commissioned by the king, but instead features the artists’ own ideologies and thoughts.

Sources

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Art_of_ancient_Egypt

- https://www.ancient.eu/Narmer_Palette/

- http://www.ancientegyptianfacts.com/ancient-egyptian-carvings.html

- https://www.ancientegyptonline.co.uk/amarnaart.html

- https://www.historylists.org/art/10-most-distinguished-works-of-ancient-egyptian-art.html

- https://www.ancient.eu/The_Great_Sphinx_of_Giza/

- https://www.ducksters.com/history/art/ancient_egyptian_art.php

- https://www.ancient.eu/article/1077/a-brief-history-of-egyptian-art/

- https://earthnworld.com/10-most-famous-monuments-of-ancient-egypt/

- https://discoveringegypt.com/egyptian-hieroglyphic-writing/

- https://www.britannica.com/topic/hieroglyphic-writing/images-videos/media/265021/119992

- https://www.britannica.com/topic/hieroglyphic-writing/images-videos/media/265021/162627

- http://luxortimesmagazine.blogspot.com/2015/03/arce-unearth-18th-dynasty-tomb-in-qurna.html

- https://www.ancientegyptonline.co.uk/nefertitibust.html

- http://artcentron.com/2014/08/02/abstract-figures-behind-islamic-patterns/